Happy New Year! I hope you all managed some sort of rest and recuperation over Christmas.

As attention turns to what looks set to be another rollercoaster term, teachers and leaders across the land are once again charged with supporting their pupils, parents and communities through extremely choppy waters.

Omicron has rocked the boat, but onwards we must sail.

And it is with that in mind that I write today, not about the pandemic, but about that other almighty boulder hurtling in our direction – the new Curriculum for Wales (CfW).

Promising a seismic shift in the way teaching and learning takes place in Wales, the curriculum is, as a former education minister once described, part of a package of reforms that is the biggest ‘anywhere in the UK for half a century’.

Reforms that are not to be taken lightly, therefore.

But as the clock ticks down to CfW’s first official launch in September – a mere two terms hence – we are not, by my reckoning, in a particularly strong place.

Putting the ongoing health crisis to one side for a moment, I genuinely believe that, to use Covid parlance, we are as a nation well behind the curriculum curve.

Let me indulge you for a moment with some sort of explanation…

Implementation plan

My first concern relates to our curriculum implementation plan – and the careful piecing together of a roadmap for curriculum roll-out.

Question is, if I were asked today what that plan actually looked like, and how successful we’d been in putting said plan into action, I’m not sure I’d have much of an idea how to respond.

Do we know, beyond all reasonable doubt, who was responsible for what and when?

Was it clear how the different ‘tiers’ of our education system would interact and support schools to turn vision into reality?

Fundamentally, was there a shared understanding of the curriculum’s aims and objectives – and were educators at all levels working towards the same goal?

The answer may lie in the Welsh Government’s all-singing and all-dancing ‘National Mission’.

The go-to education policy document for 2017-21, the National Mission ‘sets out how the school system in Wales… will move forward over the period up until 2021 to secure the effective implementation of a new curriculum’.

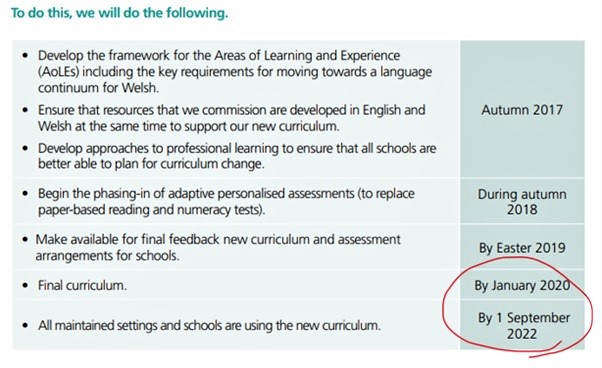

In it, policymakers offer a brief outline of activity to support curriculum roll-out (copied, with artistic licence, below):

Now there are a few things here open to challenge, but what strikes me is not so much what is written, as what isn’t.

Anyone else spot the gap between ‘final curriculum’ by January 2020, and ‘all maintained settings and schools are using the new curriculum’ by September 2022?

That’s almost three calendar years of unscripted drift according to this particular outline – the curriculum framework lands and then, as if by magic, it’s found its way into classrooms up and down the country.

OK, so that’s not entirely accurate, and I accept that a great deal of work has been undertaken since CfW documents were released formally into the system.

But National Mission actions are noticeably high-level, and the document does not detail exactly how the profession will be supported to put the new curriculum into effect.

That the Welsh Government’s own flagship education strategy did not weave in far more plainly an ‘implementation phase’ – to bridge the gap between January 2020 and September 2022 – is to me a serious design flaw.

It does not mean, as I have suggested previously, that no planning for curriculum roll-out or readying of the education workforce has taken place in the intervening period (by government or otherwise) – I accept and fully appreciate that.

But the omission of a cast iron and clearly defined implementation phase – involving a very clear and strategic professional learning programme for teachers and leaders – has arguably resulted in the ‘pot luck’ position in which we find ourselves today.

Indeed, it could explain why so many in our profession feel unsupported and barely able to keep their heads above water (I entertain similar conversations with teachers on a near weekly basis).

It’s as if we published the ‘final curriculum’ (and its 251 pages of guidance) and then said to teachers: ‘Here’s everything you need, now start engaging with it…’

Only it wasn’t everything they needed and there were gaps – big gaps. It wouldn’t have taken too many Teams calls with teachers to draw that conclusion.

Tackling the CfW guidance cold is a bit like falling down a rabbit hole – unless you know what you’re looking for and where to find it, it’ll take you a while to burrow your way out again.

Ultimately, it all boils down to this – we could have the most exciting, inspiring and ‘transformational’ new curriculum framework in the world… but if the profession doesn’t know what to do with it, the whole thing is rendered totally and utterly meaningless.

It’s worth repeating at this point that the successful implementation of CfW is completely reliant on teachers and leaders. That’s it. It really is that simple.

So the question has to be asked – why have we been so willing to let our industrious education workforce, battered and bruised by the unprecedented events of the past two years, ‘get on with curriculum reform’ (another unfortunate phrase doing the rounds) by themselves?

Why have we let them flounder amid a sea of longwinded, inaccessible and, let’s face it, very often unhelpful curriculum guidance?

Why haven’t we built in strong enough support mechanisms to give those at whatever stage in their curriculum journey confidence that they are on the right path?

If teachers and leaders are our foot soldiers – the army upon which everything else depends – then why on earth haven’t we gone into battle with them?

In far too many cases, we’ve let schools take on the daunting challenge of curriculum change by themselves.

And what’s more, we haven’t equipped them nearly well enough to do the Donaldson masterplan justice.

I’m sorry, but if you’re going to thrust on our already tired and weary profession (hands up who remembers the ‘reform fatigue’ cited by the OECD in 2014?) the most radical set of reforms in a generation, then you’re absolutely going to make sure that they have the tools they need to deliver on them.

Or at least, that’s what should have happened.

Which brings me neatly onto my second, and enduring, concern – professional learning.

Professional learning

I’ve written before on what I’d like to see done differently – and why a truly national professional learning programme, that is consistent and available to all, is very much needed.

A foundational introduction to curriculum design, that can be as detailed or abstract as the profession wants, would go some way to levelling the playing field and give teachers wherever they are in Wales access to the same learning materials.

I conceptualised in an earlier blog where I believe many in our system to be currently sat – between two worlds, waiting for a way out.

But I repeat, we cannot expect teachers at any stage of their professional careers to jump seamlessly from a culture of regulation to one of autonomy, unaided.

They must be supported in making that passage through, which requires careful transition from old to new.

Failure to do so risks leaving hundreds, if not thousands of school staff (and, by default, their pupils) languishing in the void.

The government’s reluctance to step in appears to stem from a nervousness around prescription, and a slipping back into the more ‘traditional’ practice of telling teachers what to do and when.

Policymakers are conscious of the ‘creeping hand’ of government and keen to avoid any suggestion that central diktat is back on the agenda.

But this can be very easily sidestepped – and there is a difference between government leading and government facilitating.

If we work on the basis that teachers should be inputting into anything produced to support them, then we will hopefully steer clear of at least some of the pitfalls associated with ‘official’ documentation.

It wouldn’t take a great deal of time and effort to get together a group of teachers, leaders, representatives from other key groups and known experts in their field to start thrashing out a workable plan for the future.

Whatever government decides to do next, it would make most sense to ask those whose job it is to put CfW into action what more support they need – and what they’re not getting at the moment.

It should be teachers telling policymakers what good professional learning looks like – not the other way around.

And while we’re on the subject, might we have a bit more faith in our own system?

Far too often in Wales our stock response to a professional challenge is to look outward and bring expertise in from further afield.

The working assumption is, therefore, that Wales is unable to address its own problems and almost solely reliant on external support to guide us through.

That may or may not be true in certain circumstances, and there is always much to learn from the experience of others – but on the whole, I would like to see us have far more confidence in the capacity of our own practitioners to find solutions to issues that affect them the most.

I have been fortunate in recent years to work with educators – in various roles and with various responsibilities – from across the world, and I can safely say that what we have here in Wales rivals anything I’ve seen elsewhere.

Question is, how willing are we to tap into this as yet underused resource – and, perhaps more pertinently, what is preventing us from doing so?

Now I know what some will say – the regional consortia have been supporting professional learning, and there is plenty out there available to schools should they want it.

But that is part of the problem. Since inception and by design, the consortia have been doing their own thing, co-operating occasionally on projects of mutual interest.

There is no consistent, national approach – and that is not necessarily the regions’ fault.

They are employed to support schools in their composite local authorities. They function as they were supposed to function.

But that does not for a minute mean that every school is getting what it needs. I defy anyone who says there is not huge variation in the professional learning offer available; both in terms of access and quality.

This leads to mixed messaging, an almost constant unveiling of shiny new packages and projects (in some cases, based on little or no evidence), and a competitive edge that is not conducive to the ‘team Wales’ so often championed and revered.

In essence, we need something that binds us together…

A consistent message

With mixed messaging from government and the so-called ‘middle tier’, there is little wonder that, at a school-level, teachers are being drawn into practice that our new curriculum has sought to avoid.

Lesson plans founded on Statements of What Matters; assessment tools that mark off Descriptions of Learning; and, in some cases, attempts to benchmark against the Four Purposes.

But rather than criticise schools for ‘misunderstanding the curriculum’ (we’ve all heard that one before – and from those who really should know better), shouldn’t we instead be asking why they’ve gone down this route – and what more could be done to ensure CfW is interpreted in the way in which it was intended?

It is genuinely alarming that six years into our curriculum expedition, there is still so much confusion around what the curriculum actually means.

Notwithstanding the obvious and deliberate need for local adaptation, I’d imagine it be very difficult for anyone – policymaker, middle tier, teacher, leader – to pen on a side or two of A4 a consistent message on the fundamentals of CfW.

If I were to ask you to write down your five key characteristics; your five key building blocks; your five key principles that underpin CfW – chances are, we’d all end up with something different in our notepads.

Is that really what Donaldson had in mind when he first hatched our new national curriculum?

We need to go back to the drawing board and decide what all teachers need to know and do the same – and conversely, what exactly they are permitted to do differently in their own context.

Fixed and flexible, tight and loose – frame it how you like, we need to accept that for our curriculum to be representative of the population it serves, there has to be some level of agreement on what we all do in lockstep.

I offer the following as a visual representation of what this might mean in practice…

Think of how we engage with CfW as being something like the structure of a house.

The Four Purposes are the foundations on which our new curriculum is established.

Our aforementioned curriculum guidance provides a structure from which teachers can build.

Inside is where school-based discussion takes place – this is, in effect, the space for innovation and where school staff come together to work through the finer detail of CfW and what it means for them and their learners.

For me, what’s missing is the roof and the overarching key principles that steer everything that happens beneath.

Failure to pin down the roof leaves the creative space for teaching and learning exposed to inclement and changeable weather – or in this case, shifting or outright bad advice.

It gives rise to unintended consequences and a deep-rooted feeling of insecurity that someone, somewhere won’t approve of what you’re doing.

In short, the metaphorical house is incomplete without its cover and the guiding messages that shape the profession’s interaction with CfW more generally.

All aspects of the build are common across settings – the foundations, the walls and the roof – apart from the internal teacher-to-teacher collaboration that has to be school-led.

Taking the analogy a little further, one might consider the curriculum house as being part of an estate; with an expectation that schools get to know their neighbours a little better so as to plan for a more coherent learning journey.

In the first instance, this might mean inviting the family from down the road in for a cuppa or to show them your new drapes.

Who knows, in time and as you get to know more about each other’s interests, occasional visits might evolve into something more concrete.

I’ll stop there, but you see where I’m going with this.

If nothing else, the government needs to get its work gloves back on and finish what it started.

Build consensus around the curriculum’s key principles – and share far and wide so everyone sings from the same hymn sheet.

But only do so in close consultation with the profession; they are both the architect and the craftspeople of this particular project.

As a first step, I’d begin by taking a hammer and chisel to existing curriculum documentation and remould it into something more accessible to teachers.

Those I work with don’t have the time to be trawling through protracted papers that in many cases serve only to add to the haze.

Guidance should be streamlined, broken down into bitesize chunks and housed on a website that is better signposted for those battling the ever-changing Covid landscape.

A learned friend and colleague talks about the requirement for ‘entry points’ into the new curriculum, dependent on individual practitioner proficiency; an interesting concept, with good merit.

But that assumes at least a decent understanding of CfW, and does not necessarily respond to the need for standardised information that is applicable to all.

In Scotland, a ‘Statement for Practitioners’ was published in 2016 – a full six years after its Curriculum for Excellence started rolling out in schools – in response to OECD concerns that bureaucracy was stymieing meaningful collaboration.

The statement, so says government agency Education Scotland, ‘provides key messages about what teachers and practitioners are expected to do to effectively plan learning, teaching and assessment for all learners, and also suggests what should be avoided’.

A similar document could be used to help teachers in Wales begin their engagement with curriculum guidance with a view to supporting them in the careful art of curriculum design.

Paralysis

My final point alludes to one I made earlier, and is perhaps what brings this whole blog together.

Hand on heart, and on the basis of several conversations I’ve had with very many people over the past six months or so, I am of the view that the Welsh Government is in what can only be described as a state of paralysis.

Policymakers find themselves wedged between a rock and a hard place – frozen by fear of overstepping the very fine line between subsidiarity and specification.

After years of preaching ‘power to teachers’, they don’t want to be seen as eroding autonomy by mandating any new material and/or professional support.

It’s as if policymakers know there are issues – with implementation, with professional learning and with consistency in messaging – but they can’t work out how to address them without impinging on teacher agency.

The same could also be said of curriculum content, accountability and assessment; they don’t know what to do for the best.

One only has to look at recent debates around the omission of key terms in the Relationships and Sexuality Education Code; a lack of detail in the promised teaching of Black, Asian and minority ethnic experiences; and the planned integration of separate science and English GCSEs into combined awards to see how these issues play out in reality.

Let’s be clear, the transition from prescription to what sociologist Michael Young (2008) terms ‘genericism’ is not easy, and there are very clear tensions to be overcome.

But it’s not as if these tensions are unique to our situation and the same dilemma has been entertained a number of times before.

Claire Sinnema, an authority on curriculum development in New Zealand, offers the following assessment:

‘Consideration of balance between prescription and autonomy is central to the work of designing a national curriculum. Without sufficient prescription, learners’ curriculum entitlement cannot be assured. Without sufficient freedom, teacher agency and opportunities to operate as professionals with autonomy is put at risk.’

(Sinnema, 2017, p30)

A cursory glance over the educational literature tells you all you need to know on this score – researchers are in broad agreement that there is a careful balance to be struck; between tight and loose, between fixed and flexible, between prescription and autonomy.

In my opinion, we’ve got the balance slightly wrong – and taken this notion of autonomy a little too literally.

We are, I believe, guilty of letting too many teachers ‘go it alone’ on curriculum reform, and not providing them with nearly enough professional support.

We’ve effectively let teachers and leaders fend for themselves and outside of the ‘pioneer’ model (which was not, in my view, properly harnessed for the benefit of the wider system), left the profession to sink or swim on the basis of what they’ve heard on the grapevine or been able to pick up in the margins.

And to suggest, as a virtual room full of teachers and leaders were told shortly before Christmas, that Wales is ‘amongst the most effective countries in the world as far as professional learning is concerned’ is just (deep breath) unhelpful.

Let’s ditch the ‘world-leading’ dogma until we know it to be factually accurate – such statements are at best ostentatious and at worst, misleading.

The simple truth is that as long as there are still so many teachers asking for reassurance, validation, support and direction – we are not nearly as good as we think we are.

The hundreds of educators I’ve come into contact with over the course of the past six years are a useful yardstick in that regard.

So what next?

If anything, Covid makes a well-considered implementation plan, a standardised approach to professional learning, and the pressing need for more consistent messaging, all the more important.

Not because the virus is a challenge common across the system, but because it has robbed teachers and leaders of so much valuable preparation time; time that has instead been sucked up by isolation, staff absence and blended learning.

In the absence of a ring-fenced and lucrative professional learning budget that allows every teacher in every school regular time away from the classroom (pigs can fly), it is incumbent on government to ensure the workforce has what it needs to do more effectively what is being asked of it.

It’s tools or time and while I can understand the reluctance of government to step in and take a firmer hold of some of the more pressing curriculum issues, to sit back and do nothing would be the far bigger crime.

We can’t keep kicking the same cans down the road and whether it agrees with my interpretation or not, government has to do something.

And I’m cautiously optimistic it will.

Since his appointment as Minister for Education and Welsh Language, Jeremy Miles has only really been seen when responding to the latest Covid emergency.

A few minor policy pronouncements aside, he’s spent much of the past seven months firefighting – and that’s before you even get to matters relating to curriculum reform.

There is no doubting the magnitude of the task in hand.

Nevertheless, what has been really encouraging about the early part of the minister’s tenure is his apparent openness to challenge; Mr Miles seems very willing to listen to the full range of views and appears determined to make decisions based on reasoned judgement.

This bodes well for what promises to be an absolutely crucial next seven months, during which the curriculum and our wider reform agenda will either snap into gear or drift further off course.

And so, as we embark on what is likely to be the most significant year for education in Wales since devolution, I would encourage policymakers to break free from their stupor and use the Omicron-induced hiatus (it would be folly to announce anything major any time soon) to give serious thought to the following:

- The curriculum implementation plan;

- Our national professional learning offer, and;

- A consistency in messaging.

As a first step, let’s consider what a workable curriculum implementation plan might look like; how a national professional learning offer could accommodate the needs of all teachers; and what high-level messaging is required to knit our curriculum guidance together.

As hopeful as I am that we can find a way through some of the stumbling blocks presented here, I’ll finish with a word of warning.

If curriculum roll-out is delayed again, or worse, fails to deliver on its heady expectations, it won’t be because of Covid.

It will be because of decisions made in Cathays Park; decisions that will be informed, I hope, by those with a better understanding of what is happening on the ground.

References

- Sinnema, C. (2017) Designing a national curriculum with enactment in mind – the new Curriculum for Wales: A discussion paper. Auckland: University of Auckland.

- Welsh Government. (2017) Education in Wales: Our National Mission. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

- Young, M. (2008) From constructivism to realism in the sociology of the curriculum. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 1-2.